How Many Babies Babies Are Born Each Year in Egypt

- Enquiry commodity

- Open Access

- Published:

Childbirth care in Egypt: a repeat cross-sectional analysis using Demographic and Health Surveys between 1995 and 2014 examining use of intendance, provider mix and firsthand postpartum care content

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 20, Article number:46 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Arab republic of egypt has accomplished of import reductions in maternal and neonatal bloodshed and experienced increases in the proportion of births attended by skilled professionals. However, substandard care has been highlighted as one of the avoidable causes behind persisting maternal deaths. This paper describes changes over time in the apply of childbirth care in Egypt, focusing on location and sector of provision (public versus private) and the content of firsthand postpartum intendance.

Methods

We used v Demographic and Health Surveys conducted in Egypt betwixt 1995 and 2014 to explore national and regional trends in childbirth intendance. To appraise content of care in 2014, we calculated the caesarean section rate and the percentage of women delivering in a facility who reported receiving four components of firsthand postpartum intendance for themselves and their newborn.

Results

Between 1995 and 2014, the percentage of women delivering in health facilities increased from 35 to 87% and women delivering with a skilled birth bellboy from 49 to 92%. The percentage of women delivering in a private facility nearly quadrupled from sixteen to 63%. In 2010–2014, fewer than 2% of women delivering in public or individual facilities received all iv immediate postpartum care components measured.

Conclusions

Egypt achieved big increases in the percentage of women delivering in facilities and with skilled birth attendants. However, most women and newborns did not receive essential elements of high quality firsthand postpartum care. The large shift to private facilities may highlight failures of public providers to meet women's expectations. Additionally, the content (quality) of childbirth care needs to improve in both sectors. Immediate action is required to empathize and address the drivers of poor quality, including bereft resource, perverse incentives, poor compliance and enforcement of existing standards, and providers' behaviours moving between private and public sectors. Otherwise, Arab republic of egypt risks undermining the benefits of high coverage because of substandard quality childbirth intendance.

Background

Although substantial progress was made to meet the Millennium Development Goals, maternal and perinatal mortality remain unacceptably high in almost depression- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Globally, the largest brunt of maternal deaths occurs during labor, commitment and the immediate postnatal period, namely the peripartum period [1], and similar patterns concord for babies. The preventive and curative interventions that ameliorate maternal and perinatal survival are known and supported by rigorous show. It was thought that improving access to and utilisation of facility-based childbirth care had an important function to play in reducing preventable maternal and perinatal deaths [2, 3]. However, increasing evidence highlights that poor quality facility-based intendance challenges this supposition [4,5,6].

Egypt's population is estimated to have reached 99 million people [seven] and, after years of decline, its total fertility rate increased from 3.0 in 2008 to 3.5 in 2014 [8]. Despite potential reductions in the fertility rate more than recently [9], the country's wellness arrangement has had to provide care for an increasing number of births. For example, there were an estimated 2.7 million births in 2014, a 46% increase from 1.9 million in 2006 [10]. Although Egypt's maternal mortality ratio decreased from 174 per 100,000 alive births in 1992 to 37 in 2017 [11, 12], and its neonatal mortality rate from 31 per 1000 live births in 1992 to 12 in 2017 [xiii], effectually 960 maternal and 30,000 neonatal deaths occur annually. Thanks to a loftier density population concentrated along the banks of the river Nile and in the Nile delta and the development of a large network of health facilities, distance and lack of transport were rarely identified as avoidable factors for maternal expiry in Arab republic of egypt [xi, xiv, 15]. In contrast, substandard intendance by the obstetric team, absenteeism or poor quality of antenatal intendance, and delays in recognising issues and seeking care were identified as the most important avoidable causes of maternal decease [xiv, 16]. Moreover, big socio-economical disparities in the utilisation of facility-based childbirth care continue to exist [17].

Healthcare in Arab republic of egypt is provided by a wide spectrum of modern and traditional health care providers, ranging from governmental, parastatal, university, military machine, for-profit, not-governmental organizations (NGOs), and traditional practitioners, with variable quality and cost [xviii, 19]. The Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) is a major provider of chief, preventive and curative intendance, and has an oversight responsibility (but limited potency and chapters) to regulate private providers. During the period betwixt 2007 and 2016, Egypt had 8 physicians and 14 nurses and midwives per x,000 population [20]. A loftier proportion of wellness expenditure - 62% in 2016 - came from out-of-pocket payments [21], with just 8.1% of women anile fifteen to 49 years covered by some form of public or private health insurance in 2014 [22]. Childbirth care in public hospitals is provided under three pricing schemes – public, iqtisady (for patients enrolled with the health insurance organization, the HIO), and fondoqy ("hotel" or individual service, which enables obstetricians to admit and attend private-do patients).

In 2014, the per centum of women delivering with a skilled birth attendant (SBA) reached 92%, with 87% of women in the country delivering in a facility [22]. However, in that location is limited evidence on which sector is providing childbirth care, on quality of care, or on which women are being left behind in terms of coverage and quality. These aspects are crucial to understanding the condition of childbirth care in Arab republic of egypt and developing policies that will farther improve the well-existence of its women and children.

The objective of this paper is to describe the changes over time in the utilise of childbirth care in Egypt, focusing on the sector of provision (public versus private), and the content of this care, nationally and by region.

Methods

Information and study population

We used the five most recent Demographic and Wellness Surveys (DHS) conducted in Egypt in 1995, 2000, 2005, 2008, and 2014. In analyses, nosotros refer to the surveys using the bridge of their v-year recall periods for which details on women'southward live births were nerveless (i.east., 1995 survey: 1991–1995). DHS are cross-sectional nationally representative household surveys with a multistage cluster sampling strategy. Their model questionnaires are adapted to each state's circumstances and include questions on household and individual characteristics, fertility and family planning, maternal and child wellness and details on antenatal and childbirth care. All e'er-married women aged 15–49 years with a live nascence in the surveys' five-twelvemonth recall period were included in the analysis. We examined women's self-report of childbirth care source and the components of immediate postpartum intendance for the most recent live birth.

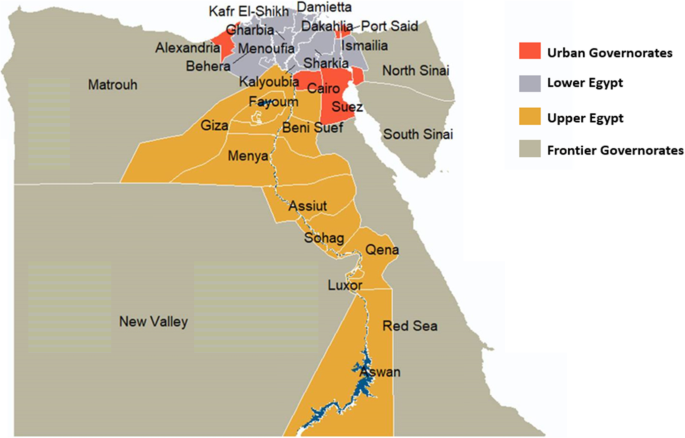

Subnational regions

All five DHS used the same half-dozen major administrative regionsto produce subnational estimates: i) Urban Governorates (four cities without rural populations: Cairo, Alexandria, Port Said, Suez), 2) urban Lower Egypt (ULE), 3) rural Lower Egypt (RLE), 4) urban Upper Egypt (UUE), 5) rural Upper Egypt (RUE), and 6) Frontier Governorates (Red Sea, New Valley, Matrouh, Northward Sinai and S Sinai governorates). Figure i depicts the 27 Egyptian governorates organised co-ordinate to the DHS' classification. In 2014, North and South Sinai were not surveyed for security reasons. While national estimates were non affected by this exclusion because only a small per centum of the total population (< 1%) resided there, the 2014 Frontier Governorates estimates should exist compared to previous surveys with caution.

Map of Egypt'south governorates as classified in the Demographic and Health Surveys adapted using data from the Humanitarian Data Commutation (HDX) [23] nether the CC By-IGO license

Definitions and analysis

Details on the indicators and definitions used in this study tin be found in Boosted file 1. In our analysis, we considered women to be in demand of childbirth care if they had a alive nascency in the survey recall period [24]. Women were considered to have had a facility delivery if they reported giving birth in whatever health facility, and assisted by an SBA if they reported being assisted past a doctor, nurse or midwife. To assess the content of childbirth care, we used four components of immediate postpartum care as proxies. These included: 1) initiating breastfeeding within an hour of birth; 2) weighing the baby; 3) checking on the woman'south health while notwithstanding in the facility; four) reporting a minimally adequate length-of-stay in the facility. We assessed the percent of women reporting receiving each component and all components.

Analysis

We first calculated the percentage of women delivering in any health facility, with a SBA and in private facilities. Then, we assessed the per centum of women delivering in facilities by sector (public and individual), in each region and by household wealth. We estimated the percentage of women receiving each of four components of immediate postpartum care and all four components, by sector of provision, type of residence, household wealth, mode of commitment (vaginal or caesarean (C)-section), and region. Information analysis was conducted in Stata SEv14 (College Station, TX), using the svyset control to account for survey blueprint of each survey (sample weights, clustering and stratification). We used tabulations and Chi-foursquare tests to provide descriptive statistics and appraise the statistical significance of different distributions. We produced estimates for each survey separately (not pooled).

Results

Study population

In full, information on childbirth intendance utilise and cardinal variables of involvement were available for 45,387 women in need of care across the five surveys, of whom 28,968 delivered in a health facility. The characteristics of the study participants, stratified by survey year, are shown in Additional file 2, while percentages, 95% confidence intervals and p-values of the data used in Figs. 2, 3 and iv tin be constitute in Additional file 3.

National trends in full and private childbirth intendance use betwixt 1995 and 2014

Between 1991 and 1995 and 2010–2014, the percentage of all women in demand of childbirth intendance who delivered in a facility increased from 35 to 87%; the per centum who delivered in private sector facilities over the same time periods increased from 16 to 63% (Fig. 2) and the percentage of women assisted past an SBA increased from 49 to 92%. On all five surveys, over 99% of women delivering in facilities reported existence attended past a doctor. Amidst women who gave nativity at home, the per centum being attended past an SBA increased from 22 to 37% over the study period. Among women delivering at habitation with an SBA in 2010–2014, 37% were attended by a doctor and 63% by a nurse or midwife.

Percentage of women in need of childbirth intendance delivering in a facility, delivering in a individual facility and delivering assisted by an SBA between 1991 and 1995 and 2010–2014

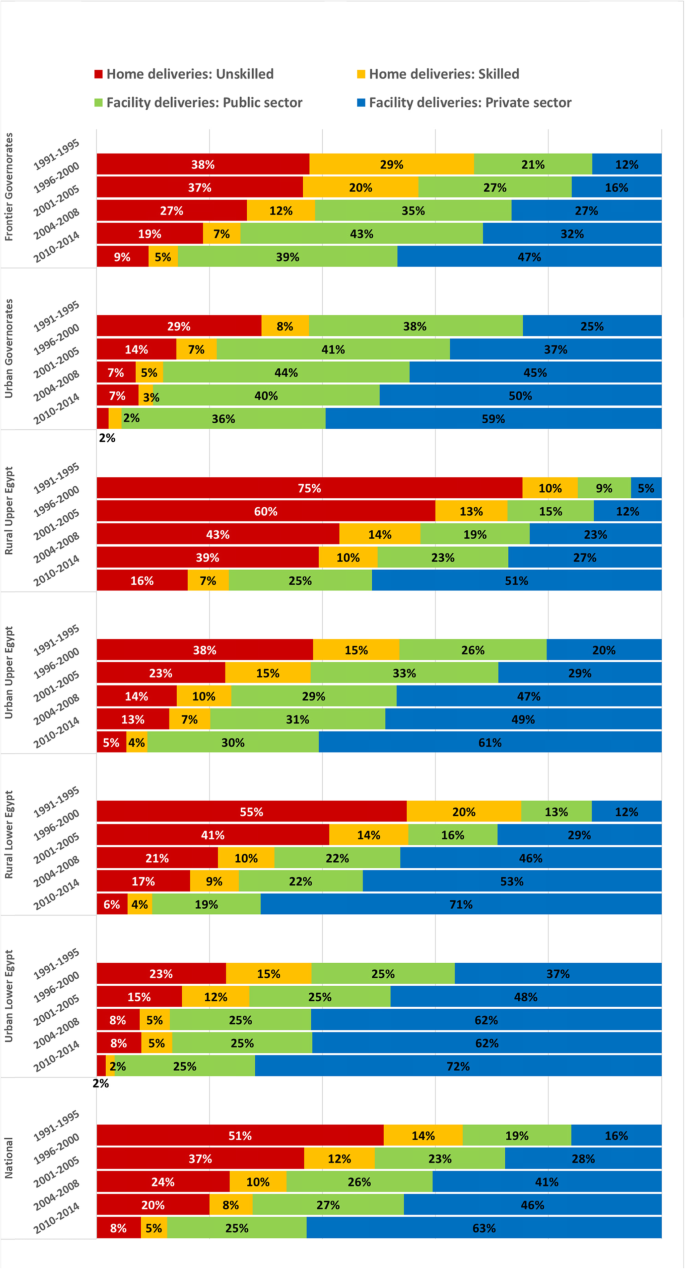

National and regional modify in facility-based childbirth and blazon of provider betwixt 1995 and 2014

The percent of women in need of childbirth intendance who delivered at abode (regardless of birth bellboy blazon) decreased in all regions between 1991 and 1995 and 2010–2014 (Fig. 3). We observed the largest absolute percentage reductions in Rural Lower Arab republic of egypt (RLE) and Rural Upper Egypt (RUE): 65 and 62 percentage points (pp), respectively. Among all women in demand of childbirth care, the percentage giving birth in public facilities increased in RLE (six pp), RUE (16 pp), Urban Upper Egypt (UUE) (xvi pp) and Borderland governorates (eighteen pp) and decreased in Urban governorates (2 pp) and Urban Lower Egypt (ULE) (one pp). The share of childbirth care occurring in private facilities increased in all regions. The largest increases were observed in RLE (59 pp) and RUE (46 pp).

Percentage of women in need of childbirth care betwixt 1991 and 1995 and 2010–2014, by location, bellboy and sector, past region

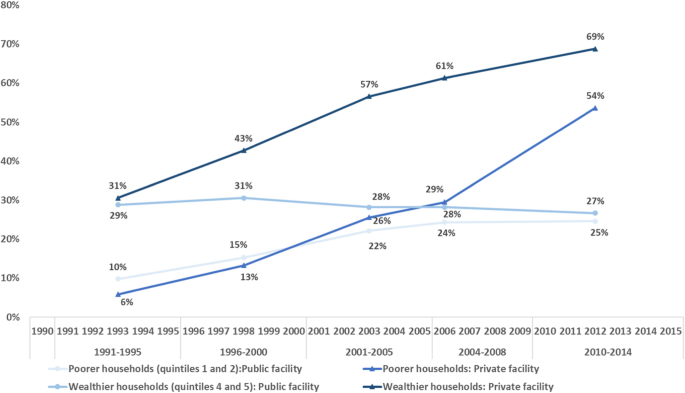

Time trends in the use of public and individual facility-based childbirth care past wealth quintile

Among women in demand of childbirth care from the two poorest quintiles, the per centum delivering in a public facility increased from viii% in 1991–1995 to 25% in 2010–2014, while the percent delivering in a individual facility rose from five to 51% (Fig. 4). Amidst women from the two wealthiest quintiles, 29% of women reported delivering in public facilities in 1991–1995, which remained virtually unchanged at 27% in 2010–2014, while the percentage who reported delivering in a private facility increased from 31% in 1005 to 69% in 2010–2014.

Percentage of women in need of childbirth intendance that delivered in a public or a private facility, stratified by household wealth

Time trends and sector differences in type of birth

The pct of women delivering past a C-section increased from vii% of all live births in 1991–1995 to 54% in 2010–2014, and from 20% of facility births to 62% during the same time periods (Table ane). Among women delivering in public facilities, the percent delivering by C-section increased from xix to 49%, compared to 22 and 67% of women delivering in private facilities. For women from the poorest 40% of households, the pct of all births by C-section increased from iii to 43%. For the wealthiest 40%, it increased from thirteen to 64%.

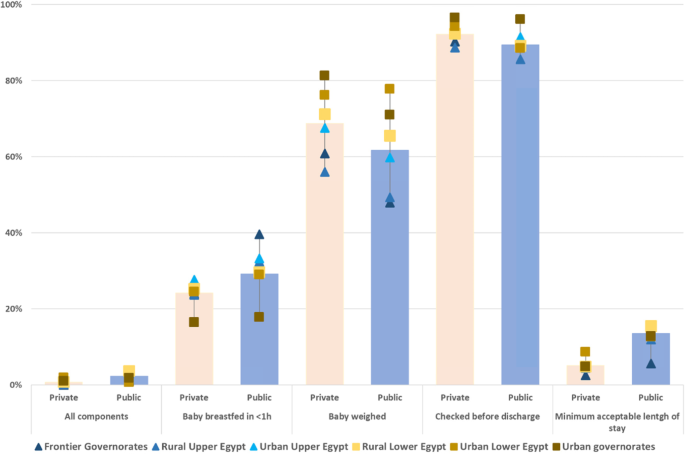

Differences in the components of immediate postpartum intendance between public and individual facilities

Tabular array ii shows the iv components of immediate postpartum intendance measured in the 2014 DHS. Of these, having the minimum acceptable length of stay was the least commonly reported care component in both public and individual facilities (fourteen and 5%, respectively, p-value< 0.001). This was followed by immediate initiation of breastfeeding (29 and 24%, p-value< 0.001). In contrast, being checked before discharge was well-nigh universal (89 and 92%, p-value< 0.001). In full, ii% of women received all 4 components in public facilities, compared to 1% of women in individual facilities (p-value = 0.001).

Looking at differences past residence, we found that in urban areas, 68% of women delivering in public facilities reported their babies were weighed, compared to 75% in private (p-value = 0.002). In urban areas, 14% of women delivering in public facilities reported an acceptable length of stay, compared to half-dozen% in private (p-value< 0.001). In rural areas, women delivering in public facilities reported their babies weighed less commonly (57%) than in private (66%, p-value< 0.001). A higher pct of rural women receiving childbirth intendance reported breastfeeding within an hr of birth (31% public, 25% private, p-value< 0.001) and an acceptable length of stay (14% public, five% private, p-value< 0.001).

Amidst users of public facilities, poorer women more commonly reported their babies were breastfed inside an 60 minutes of nascency (thirty%) compared to wealthier women (23%, p-value = 0.002). They were more than probable to report a minimally acceptable length of stay (16%, wealthier women: v%, p-value< 0.001). In contrast, poorer women delivering in private facilities more often reported their babies were weighed (59%) than wealthier women (52%, p-value = 0.002). Among women delivering in private facilities, wealthier women were more than likely to report a minimum adequate length of stay (thirteen%) compared to poorest women (half dozen%, p-value< 0.001).

Among women with vaginal births, those delivering in the public sector were more than likely to accept breastfed their newborn within an hour of birth (40%) compared to 36% in the individual sector (p-value = 0.045) and to have had an acceptable length of stay (18% in public and 11% in individual, p-value< 0.001). For having their infant weighted, the opposite design was seen: lower in public (55%) compared to private sector (63%). The sectors did not differ in the percentage of women checked before discharge.

Amongst women with a C-section, the content of care did non differ between the sectors except for the percentage reporting an adequate length of stay, which was college in public facilities (9%) than in private (two%, p-value< 0.001).

Across the 6 regions, having the babe weighed was the component with the largest absolute gap in provision, with 30 pp. between ULE and Borderland governorates for women delivering in public facilities and 25 pp. between borderland governorates and RUE in individual (Fig. 5). This was followed by breastfeeding within i h among women in public facilities (22 pp. between frontier governorates and urban governorates).

Percent of women delivering in facilities reporting receiving each component of immediate postpartum care, and all components, by region

Discussion

Betwixt 1991 and 1995 and 2010–2014, the percentage of women delivering in a health facility increased at the national level and in all regions. During this period, the private sector became the predominant provider of childbirth intendance, and the public sector declined in absolute terms. The private sector increase was observed across all regions and wealth groups. The private sector now assists more than half of the births in the country, ranging from 47% in Frontier governorates to 72% in urban Lower Arab republic of egypt. The rise in the use of private facilities began among wealthier women first, followed by poorer women starting to use private providers between 2004 and 2008 and 2010–2014. On the other hand, in 2010–2014, 13% of women in need of childbirth care did non give birth in a facility and eight% were not attended by a SBA.

The main finding of this study is that, despite the large proportion of women delivering in wellness facilities, almost none received all four basic components of immediate postpartum care captured on the 2014 DHS. This was largely driven by three components: a very depression pct of women reporting a minimum acceptable length of stay, initiating breastfeeding within an hr of birth, and having their newborn weighed. The depression provision of these intendance components used as proxies for quality of care likely shows a major quality gap that was nowadays in both public and private sectors.

We identified an important proportion of women who did not access a facility nascency or receive SBA-attended domicile-based childbirth intendance. Studies [25,26,27] in Egypt have highlighted that, in some regions, women living might still accept difficulties accessing services. For instance due to long distances and the lack of night-time or alternative emergency services at the limits of public facilities' catchment areas [25]. In Upper Egypt, some women reported distance, transportation and services' costs as barriers to access antenatal and medical treatment services [26]. In the 2004–2008 DHS recall catamenia, 63% of women delivering at home reported that giving birth in a facility was not necessary, while 23% highlighted concerns with the price of care [27]. Although free childbirth intendance should be available in public facilities in Egypt for those unable to pay for it, it has been observed that this policy failed to reach the poorest women, who end upwards delivering at abode and practise not necessarily benefit from these entitlements [17]. While public wellness insurance covers facility deliveries, poorer, less educated and rural women were less probable to be covered past wellness insurance [28].

Egypt is i of the LMICs with the highest share of women receiving childbirth care from private providers globally [24] and both socio-cultural and economic capital letter are potent determinants of facility-based childbirth care in Arab republic of egypt [17]. All the same, we observed in our written report that not only wealthy households but also the poorest have turned to private providers for childbirth care, peculiarly in the near recent period examined. The contribution of these services to families' out-of-pocket health expenses is likely to be meaning; the mean price of a birth (either vaginal or C-section) equally measured on the 2008 DHS was four times higher in private compared to public facilities [17]. Given the substantial financial brunt of such expenditure on families, the touch on of the increase in private care utilisation among women from poorer households requires further inquiry. Furthermore, the role of private providers potentially promoting unnecessary medical care must be assessed. Egypt is at present one of the countries with the highest percentage of births by C-section [29]. The C-section rate has increased consistently and is likely influenced by the use of private care [30, 31].

The significant turn to individual childbirth intendance despite its loftier price raises questions on Egyptians' perceptions of public services compared to private providers. Physicians normally work simultaneously in both public and private sectors (i.e., dual practice), and they may refer public patients to their private exercise for certain services. A survey of physicians showed that 89% had more one job, and 16% had 3 or more than [32]. Furthermore, although private services are not necessarily more than effective or efficient than public ones, they may provide more timely and hospitable services [33]. In parts of Lower and Upper Egypt, qualitative inquiry identified significant deficiencies in the care received by women in public wellness services during pregnancy and childbirth. These included lack of explanations to patients, non obtaining consent for treatment, and not respecting their right to privacy and confidentiality. Farther, some women complained of disrespectful intendance, which might exist linked to lack of adequate training in physician-patient communication and doc's limited time with patients [25]. This evidence, along with reports of high caseloads influencing doctors' management of labour [34, 35] and deficits in staffing, distribution of workforce in rural public facilities [36] can be especially relevant to understanding the shift to private care. In a nationally-representative survey, the three reasons most commonly cited as primary contributors to satisfaction across different services were perceived quality, good communication skills, and reasonable financial and physical access [37]. Egyptian women look to deliver in a caring and respectful surroundings, conditions that may often clash with their experiences with health providers [38]. Therefore, poor patient-centred care may exist a key factor behind women preferring private facilities to public ones. Indeed, our results showing that essential components of immediate postpartum care are equally low in the individual sector as in the public sector imply that the preferences for private care might be based on trust, communication, and respect rather than evidence-based intendance.

Despite the high percentage of women delivering in health facilities and with a SBA, it is unlikely that like numbers are receiving this childbirth care with adequate quality. Our analysis of the components of immediate postpartum care revealed the limitation of relying on coverage indicators of facility and SBA-attended deliveries as proxies for the percentage of women receiving good quality care or evidence-based content of childbirth intendance. This finding is aligned with existing bear witness and highlights the need to increase the focus on quality measures [iii,iv,5,6, 39]. In Egypt, the substandard provision of immediate postpartum intendance documented past our assay concurs with previous evidence [34, 35, twoscore, 41] and raises questions virtually the quality of childbirth care provided in both public and private sector facilities. This is well-illustrated by the alarmingly depression percentage of women staying for an acceptable amount of fourth dimension after birth. Egypt is one of the LMICs with the shortest length of stay for both vaginal and C-department deliveries, and the shortest length of stay for singleton vaginal deliveries – just one-half a twenty-four hour period [42]. Early discharge tin can accept negative effects on both women and newborns. For instance, it was linked to higher neonatal readmission in an Egyptian hospital [43]. The short periods of stay afterward birth are of special concern considering the increase in the per centum of C-sections in Arab republic of egypt—54% of all births in 2010–2014. For public services, previous inquiry suggests that loftier caseloads may be causing bed shortages [35], which in some areas may be exacerbated by understaffing in facilities [36]. Previous research on C-sections in public hospitals suggests that unnecessary C-sections are driven by a combination of lack of training and supervision and doctors convenience incentives (i.e. doctors choosing the shortest commitment option, in which timing can also be decided) [44]. It is possible that these factors also influence the provision of postpartum care and is unclear whether they may influence private provision too. For private services, the percentage of women reporting an acceptable length of stay was consistently lower compared to public services for wealthier and poorer households, urban and rural, and vaginal and C-section deliveries. The reasons behind this inadequate care in private facilities must be identified and addressed by policymakers. For example, it would exist important to understand what proportions of women reporting to take delivered with a private doctor (tabib khas) delivered in public facilities under the fondoqy scheme versus in individual clinics. 2d, the physical structure of private clinics needs to be explored further, including whether possibilities for a sufficient lentgh of postpartum stay exist (inpatient beds, overnight staffing and acceptable nursing care, etc.).

The proportion of women reporting breastfeeding their infant within the commencement hour was remarkably low, despite show suggesting better breastfeeding outcomes may be more than favourable in facility births compared to births at home [45]. Commitment past C-department has been observed to delay breastfeeding initiation in different settings [46,47,48,49]. In a contempo report, UNICEF and WHO observed that early initiation rates were significantly lower in newborns delivered past C-section compared to vaginal delivery in 45 out of 51 LMICs studied, including Egypt [49]. Considering the large percent of births by C-section in Arab republic of egypt [30], it is particularly relevant that guidelines and interventions are targeted to improve early breastfeeding initiation after this type of delivery. I such intervention may exist to introduce pare-to-skin contact afterwards C-sections [50]. In addition, trained staff who are knowledgeable enough to facilitate skin-to-skin and inform and support mothers in the breastfeeding process, along with monitoring systems tracking comeback, can assist support early initiation [49]. A pocket-size cross-sectional study with nursing students in Cairo observed weak breastfeeding noesis [51], while previous bear witness in the country suggests that preparation chief intendance providers to promote and back up breastfeeding can improve the capability of postnatal counselling [52]. In our study, early breastfeeding was likewise more than common in Frontier governorates and Upper Egypt and particularly depression in Urban Governorates. These differences may be influenced by differences in the percentage of C-sections [22, 53], only as well by the knowledge and preferences of mothers, providers and communities and existing initiatives supporting breastfeeding [53]. Some evidence has pointed to rural mothers existence enlightened of the benefits of breastfeeding [54], and mothers in Lower Egypt delaying breastfeeding initiation to an hour after commitment more than frequently than in Upper Egypt [55]. Future research should focus on analysing the effect of increased C-sections on breastfeeding and understand other barriers or enablers of early initiation of breastfeeding in Egypt.

In contrast to length of stay and breastfeeding initiation, nearly women delivering in a facility reported existence checked while notwithstanding in the facility before discharge. However, the DHS only asks women if someone either inquired about their health or examined them. This means that many of these women may have never received a physical or complete examination. Further enquiry would be needed to empathise to appraise whether the percentage of women who actually received a concrete exam according to guidelines earlier discharge really approximates what is reported. Similarly, the percentage of women reporting their babe weight measured was college than length of stay and breastfeeding initiation. However, 30 to 40% of women notwithstanding did not receive a adequately elementary process, despite the importance of low nativity weight equally a known chance factor [56, 57]. The causes for providers non measuring birth weight routinely, particularly in rural and poorer households, should be farther explored.

When considering why components of immediate postpartum care were provided differently across sectors, it is of import to bear in listen that different levels of enforcement, incentives and resource play a role. For instance, information technology has been highlighted that private neonatal clinics are hardly supervised or monitored by the MOHP [58]. Given that private providers nourish most deliveries, it is critical that better regulation and monitoring are put in identify. In public services, lack of adherence to guidelines, training, supportive supervision and coordinated referral systems have been documented, leaving health workers unsupported and unprepared to perform their jobs correctly [44, 59]. It is currently unclear whether private providers may experience these issues as well; greater access to information from private facilities should be required for policy and research purposes. In improver, health workers' movement to the private sector for better salaries [36, 58, sixty], leaving public facilities with less experienced staff and, sometimes, understaffed [36]. Urgent activity is required to understand and address the drivers of poor quality in all its forms, including insufficient resources in the health system, poor compliance, perverse incentives, enforcement of existing standards, and providers' behaviours moving between the private and public sector.

Immediate steps can exist fabricated towards improving the quality of childbirth care. For case, midwives can have a greater role during and right after delivery, providing services (early breastfeeding, pre-belch checks) that doctors may non take time for, and supporting women during delivery [30]. This task-shifting is likely to provide better patient-centred intendance to women and help with understaffing. Educational interventions targeting wellness providers and poor women in childbearing period could be an constructive approach to make women more aware of the care they should be provided [61]. To ameliorate inform policymaking on a timely basis, routine data drove systems need to be developed to capture quality of care in key moments before, during and after childbirth. New specialised tools are being adult to sympathize how mothers are treated during childbirth and could exist used to rail the intendance mothers receive [62]. Moreover, further resource and attending need to be placed in developing systems that collect, harmonize and make health arrangement data from both public and private providers accessible to policymakers and researchers [iv].

Limitations

This study benefited from comparable data collected in Arab republic of egypt over a period of 23 years. The limitations of this study include the fact that surveys only captured live births, thus data about women experiencing negative outcomes (e.chiliad., stillbirths, miscarriage, maternal death) is not reflected in this sample. In improver, some women have to recall care received up to 5 years ago and during which they may have received anaesthesia. These aspects may might also have affected the ability of some women to recollect whether or how they received a specific intervention. Nosotros analysed care for nearly recent live births, and thus slightly underestimated the experiences of women who had more ane live nascency in the recollect period. Moreover, DHS surveys are cross-exclusive and conducted every iv to 5 years, making impossible to follow respondents over time.

Household surveys such equally DHS and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) do not capture receipt of key intrapartum care interventions such every bit utilise of uterotonics or monitoring of progress of labour [63]. Our power to describe the content of childbirth was limited to the proxy components capturing only some aspects of clinical and process quality. As a result, important aspects such as interventions provided during commitment, the patient-provider interaction and respectful care could not be explored. Withal, the available iv elements can likely provide important signals about the quality of intrapartum intendance and certainly reveal pregnant gaps in firsthand postpartum care offered beyond the different categories of delivery systems. Given the systemic bug influencing quality of care in Egypt [58] and documented substandard intrapartum practices [34, 35], tools that tin capture better measures of quality of care during and later delivery should exist adult. Nevertheless, such information and indicators are unlikely to be nerveless from women themselves, due to poor validity [64,65,66,67]. Finally, it was not possible to assess whether women in public hospitals were in a public or a paying/private section. The private sector includes a range of providers with different service quality and capacity to provide services adequately. Due to the nature of the questions in the survey, our analysis was non capable of differentiating between these providers to appraise if critical differences exist between them. These challenges within DHS take been voiced elsewhere [68] and should considered in the design of future surveys looking into maternal health services.

Conclusion

Between 1991 and 2014, Egypt experienced remarkable improvements in the percentage of women delivering in a facility and with an SBA across all regions and wealth groups. Crucially, during this period, the private sector became the main provider of childbirth care in the land. Studying the reasons backside this shift to private childbirth intendance can provide valuable information on dimensions of quality that may demand comeback in public facilities, such every bit trust, communication and respect.

Despite the large percentage of women delivering in facilities, almost none of them reported received all the basic components of firsthand postpartum intendance captured on the 2014 DHS, regardless of sector. This evidence suggests that most providers failed to provide childbirth care co-ordinate to Egyptian or international guidelines. A combination of different factors is likely to influence substandard care, including insufficient staff, resources and grooming, lack of adherence to guidelines, inadequate supervision, and suboptimal incentives for provision of loftier-quality care. These factors demand to exist studied farther to be addressed fairly. Researchers and policymakers must prioritize understanding the determinants of substandard childbirth care and developing policies and allocating resources to address them. Until these steps are taken, Egypt is likely to miss many of the benefits that their high levels of coverage of facility deliveries would be expected to confer on maternal and neonatal wellness.

Availability of information and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current written report are bachelor in the Demographic and Health surveys repository, available at: https://dhsprogram.com/information/Using-Datasets-for-Analysis.cfm.

Abbreviations

- C-section:

-

Caesarean section

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Wellness Survey

- HDX:

-

Humanitarian Data Exchange

- HIO:

-

Health insurance organisation

- LMICs:

-

Low- and Middle-income countries

- MICS:

-

Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys

- MOHP:

-

Ministry of Health and Population

- NGOs:

-

Non-governmental organizations

- RLE:

-

Rural Lower Arab republic of egypt

- RUE:

-

Rural Upper Egypt

- SBA:

-

Skilled birth attendant

- ULE:

-

Urban Lower Egypt

- UNICEF:

-

United nations International Children's Emergency Fund

- UUE:

-

Urban Upper Egypt

- WHO:

-

Globe Wellness Organization

References

-

World Health Organization, UNICEF, UNFPA, Globe Depository financial institution Group, Un. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Banking company Group and the United Nations Population Partitioning. 2015.

-

Campbell OM, Graham WJ. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. lancet. 2006;368:1284–99 Bachelor from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17027735. [cited 2018 Aug 26].

-

Campbell OMR, Calvert C, Testa A, Strehlow Yard, Benova L, Keyes Due east, et al. The scale, scope, coverage, and capability of childbirth care. The Lancet. 2016;388:2193–208 Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(sixteen)31528-8/fulltext. [cited 2019 Jun xviii].

-

Kruk ME, Gage Ad, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan South, et al. Loftier-quality wellness systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Heal. 2018;vi(eleven):e1196–252 Bachelor from: www.thelancet.com/lancetgh. [cited 2019 Jun eighteen].

-

Fink G, Cohen J. Delivering quality: prophylactic childbirth requires more than facilities. Lancet Glob Heal. 2019;seven(eight):e990–1 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214109X19301937. [cited 2019 Aug i].

-

Gabrysch S, Nesbitt R, Schoeps A, Hurt 50, Soremekun S, Edmond K, et al. Does facility birth reduce maternal and perinatal mortality?: A secondary analysis of 2 RCTs including 119,244 pregnancies in Brong Ahafo, Ghana. Lancet Glob Heal. 2019;7(8):e1074–87 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214109X19301652. [cited 2019 Aug 1].

-

The World Banking concern Grouping. Population estimates and projections | DataBank. 2019; Available from: https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=Health-Nutrition-and-Population-Statistics:-Population-estimates-and-projections. [cited 2019 Jun 18]

-

Radovich Due east, El-Shitany A, Sholkamy H, Benova L. Rise upward: Fertility trends in Egypt before and after the revolution. PLoS One [Internet]. 2018 ;13(1). Available from: https://doi.org/x.1371/periodical.pone.0190148. [cited 2019 Jun 18]

-

UNFPA. Trends of Fertility Levels in Egypt in Recent Years [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://arab republic of egypt.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Trends of Fertility Levels Final Version 12Sept2019.pdf.

-

UNFPA. Population State of affairs Analysis of Arab republic of egypt [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Sep iii]. Available from: https://egypt.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Population Situation Analysis Web May23rd.pdf.

-

Campbell O, Gipson R, Issa AH, Matta N, El Deeb B, El Mohandes A, et al. National maternal bloodshed ratio in Egypt halved between 1992–93 and 2000. Balderdash Earth Wellness Organ. 2005;83(6):462–71 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2626255/pdf/15976898.pdf. [cited 2017 Dec 15].

-

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, United Nations Population Division. Trends in Maternal Mortality : 2000 To 2017 [Internet]. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, Globe Bank Grouping and the United Nations Population Segmentation. 2019. Available from: https://world wide web.unfpa.org/featured-publication/trends-maternal-mortality-2000-2017

-

Neonatal mortality - UNICEF Data. 2019 . Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/kid-survival/neonatal-mortality/. [cited 2019 Nov 17]

-

Campbell O, Foster Mustarde L, Hassanein N, Khalil K. How Egypt has overcome the challenges. In: Kehoe S, Neilson J, Norman J, editors. Maternal and infant deaths: chasing millennium development goals four and v. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing; 2010. Available from: http://researchonline.lshtm.ac.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland/id/eprint/1910.

-

World Health Organization. Land Cooperation Strategy for WHO and Egypt. 2010. Available from: http://applications.emro.who.int/docs/CCS_Egypt_2010_EN_14481.pdf. [cited 2017 Dec 15]

-

Gipson R, El Mohandes A, Campbell O, Issa AH, Matta N, Mansour E. The trend of maternal bloodshed in Egypt from 1992–2000: An accent on regional differences. Matern Child Health J. 2005;ix(1):71–82 Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10995-005-3348-1. [cited 2018 Aug 26].

-

Benova L, Campbell OM, Ploubidis GB. A arbitration arroyo to understanding socio-economical inequalities in maternal health-seeking behaviours in Egypt. BMC Wellness Serv Res. 2015;fifteen(1):1 Available from: http://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-014-0652-8.

-

World Wellness System. EMRO Health System Contour: Egypt. 2006. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s17293e/s17293e.pdf

-

USAID, El-Zanaty Associates, Ministry of Health and Population. Egypt Service Provision Cess Survey 2004. 2005. Available from: www.measuredhs.com. [cited 2018 Aug 26]

-

World Health System. Globe Health Statistics: monitoring health for the sustainable development goals. Geneva: Globe Health Statistics: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals; 2018. Bachelor from: https://world wide web.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2019/en/

-

The Globe Depository financial institution Group. Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of electric current health expenditure) | Data. 2019. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS?locations=EG. [cited 2019 Jun eighteen]

-

Ministry of Wellness and Population of Egypt, El-Zanaty and Associates, ICF International. Egypt Demographic and Wellness Survey 2014. 2015. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR302/FR302.pdf. [cited 2018 Dec 3]

-

Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX). Available from: https://information.humdata.org/dataset/egypt-authoritative-boundaries-levels-0-3

-

Campbell OMR, Benova L, Macleod D, Baggaley RF, Rodrigues LC, Hanson M, et al. Family unit planning, antenatal and delivery care: cantankerous-sectional survey evidence on levels of coverage and inequalities past public and private sector in 57 low- and eye-income countries. Trop med Int heal. 2016;21(4):486–503 Bachelor from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26892335.

-

UNICEF, Egybiotech. Gender analysis for factors affecting use and provision of wellness services in areas of the integrated perinatal health and child diet Programme [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/egypt/research-and-reports

-

Chiang C, Labeeb SA, Higuchi One thousand, Mohamed AG, Aoyama A. Barriers to the use of basic health services amid women in rural southern Egypt (Upper Egypt). Nagoya J Med Sci. 2013;75(iii–4):225–31 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24640178. [cited 2017 Dec 8].

-

El-Zanaty F, Way A. Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 2008. 2009. Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR220/FR220.pdf. [cited 2019 Aug 3]

-

Rashad AS, Sharaf MF, Mansour EI. Does public wellness insurance increase maternal health care utilization in Egypt?. 2016. Bachelor from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jid.3414. [cited 2019 Aug 5]

-

Boerma T, Ronsmans C, Melesse DY, Barros AJD, Barros FC, Juan 50, et al. Global epidemiology of employ of and disparities in caesarean sections. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1341–8 Bachelor from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/scientific discipline/article/pii/S0140673618319287?via%3Dihub. [cited 2018 December 3].

-

Abdel-Tawab Northward, Oraby D, Hassanein N, El-Nakib South. Cesarean department deliveries in Egypt: trends, practices, perceptions, and cost. 2018; Available from: https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2018PGY_CesareanSectionEgypt.pdf

-

Al Rifai RH. Trend of caesarean deliveries in Egypt and its associated factors: Bear witness from national surveys, 2005-2014. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):417 Bachelor from: http://world wide web.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29237410. [cited 2018 Sep 3].

-

DFID Health systems resource Centre. Multiple public-private jobholding of health care providers in developing countries 2004; Available from: http://www.heart-resources.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Multiple-public-private-jobholding-of-healthcare-providers.pdf

-

Basu Due south, Andrews J, Kishore S, Panjabi R, Stuckler D. Comparative operation of private and public healthcare systems in depression- and heart-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2012;9(half dozen):19 Bachelor from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22723748. [cited 2019 Aug 5].

-

Cherine M, Khalil K, Hassanein North, Sholkamy H, Breebaart M, Elnoury A. Management of the tertiary stage of labor in an Egyptian teaching hospital. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;87(one):54–8 Bachelor from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15464784. [cited 2018 Aug 26].

-

Khalil Grand, Cherine Thousand, Elnoury A, Sholkamy H, Breebaart M, Hassanein N. Labor augmentation in an Egyptian teaching infirmary. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2004;85(ane):74–80 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15050479. [cited 2019 Aug 1].

-

UNICEF, Egybiotech. Qualitative report on barriers and bottlenecks to effective perinatal care in rural Arab republic of egypt. 2013. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/egypt/research-and-reports

-

Rafeh N, Williams J, Hassan N. Egypt Household Health Expenditure and Utilization survey 2010. 2011. Bachelor from: https://www.hfgproject.org/egypt-household-health-expenditure-utilization-survey-2010/

-

El-Nemer A, Downe S, Pocket-sized N. 'She would assistance me from the heart': An ethnography of Egyptian women in labour. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(1):81–92 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/scientific discipline/commodity/abs/pii/S027795360500242X. [cited 2019 Oct 12].

-

Radovich E, Benova Fifty, Penn-Kekana L, Wong K, OMR C. Who assisted with the delivery of (Proper noun)?' Problems in estimating skilled birth attendant coverage through population-based surveys and implications for improving global tracking. BMJ Glob Heal. 2019;4(two):e001367 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31139455. [cited 2019 Aug v].

-

Khalil One thousand, Elnoury A, Cherine G, Sholkamy H, Hassanein North, Mohsen L, et al. Infirmary practice versus testify-based obstetrics: categorizing practices for normal nascency in an Egyptian teaching hospital. Birth. 2005;32(4):283–ninety Available from: http://world wide web.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16336369. [cited 2019 Aug 5].

-

Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard G, Ciapponi A, Colaci D, Comandé D, et al. Beyond as well piddling, also late and besides much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity intendance worldwide. The Lancet. 2016;388:2176–92 Bachelor from: https://world wide web.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-67361631472-half dozen/fulltext. [cited 2019 Aug 5].

-

Campbell OMR, Cegolon L, Macleod D, Benova L. Length of stay after childbirth in 92 countries and associated factors in thirty low- and center-income countries: compilation of reported data and a cross-sectional analysis from nationally representative surveys. PLoS Med. 2016;thirteen(3):i–24 Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001972.

-

Bayoumi YA, Bassiouny YA, Hassan AA, Gouda M, Sameh South, Abdelrahman Z, et al. Is in that location a difference in the maternal and neonatal outcomes betwixt patients discharged afterward 24 h versus 72 h following cesarean section? A prospective randomized observational report on 2998 patients. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2017;29(eight):1339–43 Available from: http://world wide web.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ijmf20. [cited 2018 Sep 5].

-

Elnakib S, Abdel-Tawab N, Orbay D, Hassanein N. Medical and non-medical reasons for cesarean department commitment in Arab republic of egypt: a infirmary-based retrospective report. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):i–11 Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-019-2558-2.

-

Oakley L, Benova L, Macleod D, Lynch CA, OMR C. Early on breastfeeding practices: Descriptive analysis of recent Demographic and Wellness Surveys. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(2):e12535 Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/mcn.12535. [cited 2019 Aug 2].

-

Zanardo 5, Svegliado G, Cavallin F, Giustardi A, Cosmi E, Litta P, et al. Constituent Cesarean Commitment: Does Information technology Have a Negative Outcome on Breastfeeding? Birth. 2010;37(4):275–nine Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00421.10. [cited 2019 Aug two].

-

Takahashi K, Ganchimeg T, Ota E, Vogel JP, Souza JP, Laopaiboon G, et al. Prevalence of early on initiation of breastfeeding and determinants of delayed initiation of breastfeeding: secondary assay of the WHO global survey. Vol. 7, scientific reports: Nature publishing group; 2017. p. 44868. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28322265. [cited 2019 Aug 2]

-

Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig MJ, Cohen RJ. Risk Factors for Suboptimal Infant Breastfeeding Beliefs, Delayed Onset of Lactation, and Excess Neonatal Weight Loss. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3):607–19 Available from: http://world wide web.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12949292. [cited 2019 Aug 2].

-

UNICEF, WHO. Capture the Moment – Early initiation of breastfeeding: The best offset for every newborn: Unicef; 2018. p. one–42. Bachelor from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/infant-and-young-kid-feeding/. [cited 2019 Aug 2]

-

Stevens J, Schmied Five, Burns Eastward, Dahlen H. Immediate or early peel-to-skin contact afterward a Caesarean section: A review of the literature. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10:456–73 Bachelor from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/mcn.12128?casa_token=GBk0ANuDa1EAAAAA:g511eqtiLWrGcP76mX1fVk5lFzeyvaAhnXIU4Ey7CcZc8QvQV3p6d1Pa6nzkGzU_0oAYEzYfgZzcxg. [cited 2019 Aug ii].

-

Ahmed A, El Guindy SR. Breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes among Egyptian baccalaureate students. Int Nurs Rev. 2011;58(3):372–8 Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ten.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00885.x. [cited 2018 Sep 5].

-

Abul-Fadl PAM, Mohamed PEAB, Abu PO, Shady BDOG, DMM F, et al. How Much Grooming Tin can Change Antenatal Care Practices in Counseling and Breatfeeding Promotion? MCFC-Egyptian. J Breastfeed. 2016;12:43–56 Bachelor from: http://www.mcfcare.org/Journal/Volume/Vol_12.pdf.

-

Prior E, Santhakumaran S, Gale C, Philipps LH, Modi N, Hyde MJ. Breastfeeding later on cesarean delivery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of globe literature. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(5):1113–35 Available from: https://world wide web.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22456657. [cited 2019 Dec 23].

-

Mohammed East, Ghazawy E, Hassan E. Cognition, attitude, and practices of breastfeeding and weaning among mothers of children up to two years quondam in a rural area in el-minia governorate, Egypt. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2014;3(2):–136 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25161971. [cited 2018 Sep 5].

-

Abul-Fadl AMAM, Shawky Thou, El-Taweel A, Cadwell K, Turner-Maffei C. Evaluation of Mothers' Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice Towards the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding in Egypt. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(three):173–eight Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22803928. [cited 2018 Sep five].

-

Hong R, Ruiz-Beltran M. Low birth weight as a risk factor for infant mortality in Egypt. East Mediterr Heal J. 2008;14(5):992–1002 Bachelor from: http://world wide web.emro.who.int/emhj-volume-fourteen-2008/volume-14-consequence-5/low-nascence-weight-every bit-a-run a risk-factor-for-infant-bloodshed-in-arab republic of egypt.html.

-

Mansour E, Eissa AN, Nofal LM, Kharboush I, Reda AA. Morbidity and mortality of low-birth- weight infants in Egypt. 2005;xi(4):723–31 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16700389.

-

UNICEF, Centre for Development Services. Barriers to effective neonatal referral system and quality service delivery in Arab republic of egypt. 2015. Bachelor from: https://www.unicef.org/arab republic of egypt/enquiry-and-reports

-

UNICEF. Reaching Universal Health Coverage through Commune Wellness Organisation Strengthening: Using a modified Tanahashi model sub-nationally to attain equitable and constructive coverage [Internet]. Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Working Paper, UNICEF Health Section. 2013 [cited 2017 Dec viii]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/wellness/files/DHSS_to_reach_UHC_121013.pdf

-

World Bank. Intensive learning implementation completion and results report. 2010. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/713771468236044169/pdf/ICR11620ICR0P01closed0april03002010.pdf. [cited 2018 Sep 3]

-

Metwally AM, Saleh RM, El-Etreby LA, Salama SI, Aboulghate A, Amer HA, et al. Enhancing the value of women'southward reproductive rights through community based interventions in upper Egypt governorates: a randomized interventional report. Int J equity health. 2019;eighteen(i):1–10 Bachelor from: https://world wide web.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31533741.

-

Bohren Chiliad. development of tools to measure out how women are treated during facility-based childbirth in 4 countries: L ascertainment and community survey 11 M and HS 1117 PH and HSA, Vogel JP, Fawole B, Maya ET, Maung TM, Baldé Doctor, et al. Methodological evolution of tools to mensurate how women are treated during facility-based childbirth in 4 countries: Labor observation and community survey 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services. BMC Med Res Methodol, fifteen. 2018;18(1):1 Available from: https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/manufactures/10.1186/s12874-018-0603-x.

-

Bryce J, Arnold F, Blanc A, Hancioglu A, Newby H, Requejo J, et al. Measuring Coverage in MNCH: New Findings, New Strategies, and Recommendations for Action. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5) Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=ten.1371/journal.pmed.1001423.

-

Stanton CK, Rawlins B, Drake M, Dos Anjos M, Cantor D, Chongo L, et al. Measuring coverage in MNCH: testing the validity of women's cocky-report of key maternal and newborn wellness interventions during the peripartum menses in Mozambique. PLoS One. 2013;viii(5):e60694 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23667427. [cited 2017 Dec 15].

-

Blanc AK, Diaz C, Mccarthy KJ, Berdichevsky Chiliad. Measuring progress in maternal and newborn wellness care in Mexico : validating indicators of wellness arrangement contact and quality of care. BMC pregnancy childbirth. 2016:ane–11. Bachelor from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27577266.

-

Blanc AK, Warren C, McCarthy KJ, Kimani J, Ndwiga C, RamaRao Due south. Assessing the validity of indicators of the quality of maternal and newborn health care in Republic of kenya. J glob health. 2016;vi(1):1–13 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27231541.

-

McCarthy KJ, Blanc AK, Warren CE, Mdawida B. Women's call up of maternal and newborn interventions received in the postnatal period: a validity report in Kenya and Swaziland. J glob health. 2018;8(1) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29904605.

-

Footman M, Benova L, Goodman C, Macleod D, Lynch CA, Penn-Kekana 50, et al. Using multi-country household surveys to understand who provides reproductive and maternal wellness services in low- and middle-income countries: A disquisitional appraisal of the Demographic and Wellness Surveys. Trop Med Int Heal. 2015;xx(v):589–606 Available from: http://userforum.dhsprogram.com/. [cited 2019 Feb 10].

-

Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data - Or tears: An awarding to educational enrollments in states of Bharat. Census. 2001;38(1):115–32 Bachelor from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3088292?origin=crossref. [cited 2018 Sep three].

-

Rutstein SO, Johnson Chiliad. The DHS Wealth Index. DHS Comp Reports No half dozen. 2004;6:ane–71 Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/CR6/CR6.pdf.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful for Demographic and Health Surveys for putting these information in the service of scientific discipline and for the women participating in these surveys. The authors would likewise like to express their gratitude to Dr. Nahla Abdel-Tawab from Population Council Egypt for providing key insights for the discussion and recommendations. The author would also similar to give thanks Dr. Kerry Wong from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for her back up creating the map of Egyptian governorates.

Funding

Some of the authors (LB, ER, MP) of this paper were partly supported past funding from MSD (Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp) through its MSD for Mothers programme. MSD had no office in the design, collection, assay and interpretation of information, in writing of the manuscript, or in the conclusion to submit the manuscript for publication. The content of this publication is solely the responsibleness of the authors and does non stand for the official views of MSD. MSD for Mothers is an initiative of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, N.J., U.S.A.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

MPG, LB, OMRC and ER conceptualised the study. LB and ER standardised the datasets. MPG led the assay of the information with inputs from LB, ER, OMRC, NH and KK. MPG and LB wrote the showtime typhoon of the manuscript, which was revised, finalised and canonical by ER, OMRC, NH, and KK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Respective writer

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The DHS receive authorities permission and follow ethical practices including informed consent and balls of confidentiality. Before interviews started, respondents were informed nearly the purpose and elapsing of the interviews. They were given the proper noun of the agency that was conducting the survey and informed that their participation was voluntary, and that they could stop the interview at any time. Respondents were told that all information provided would be kept confidential and de-identified to protect their anonymity. They were given an opportunity to ask the survey enumerator whatever questions. The enumerator asked them whether they consented to participate. Such verbal consent, if obtained, was noted on the questionnaire with a signature of the enumerator and the date before the commencement of the interview. Egypt'southward Institutional Review Board ensured that the survey complied with national laws and norms. The Research Ideals Committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine approved our secondary-information assay.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilize, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided yous give appropriate credit to the original writer(south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the information made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Virtually this article

Cite this article

Pugliese-Garcia, M., Radovich, E., Campbell, O.M.R. et al. Childbirth intendance in Egypt: a repeat cross-sectional analysis using Demographic and Health Surveys between 1995 and 2014 examining use of care, provider mix and immediate postpartum care content. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 46 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2730-8

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2730-8

Keywords

- Childbirth intendance

- Commitment intendance

- Egypt

- Quality

- Demographic and health survey

- Caesarean department

- Postpartum intendance

- Breastfeeding initiation

- Early on discharge

- Length of stay

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-020-2730-8

0 Response to "How Many Babies Babies Are Born Each Year in Egypt"

Post a Comment